I’m 1/12 First Nations

8% of me is a Mohawk of the Bay of Quinte. I have Indian Status, which affords me many benefits including health care, tax exemptions, educational opportunities, and more.

Having this status has always just been a sweet perk to me. Outside of my Indian Status, I’ve always had great health coverage; through my parents, through my university, and now my work. Though I needed the help of student loans to do the university thing, I had enough opportunity before university and during university to pay back my loan in good time, and start developing some savings. I had no struggling family members that needed my help. Nothing expected of me. I’ve been free to earn, save, live, and have fun all my life.

Many of the benefits of my Indian Status I don’t use. Mostly because I don’t need to. The only times I’ve used it was for the purchase of a couch, and 2 used cars. Not paying tax on those items was a sweet break. But it didn’t make or break those purchases.

With all that’s gone on in recent years with Indigenous peoples in Canada and the process of reconciliation that the government has begun, I feel like a wolf in sheep’s clothing. I benefit from the plight of the First Nations people that I’m related to by heritage, but have never experienced the pain and hurt that has afforded me all the benefit that I don’t really need.

So I’m diving in. I want to know more about my heritage, and perhaps discover that I want to own more of that status than I have before.

Finding my ancestors

As I entered university, my dad was starting the process that I’m now embarking on. I think things got stirred up for him when my grandmother, his mother, Thelma, passed away the summer of 2005, just before I went off to campus for my first year. This was a big loss for my Dad, whose father passed away when he was young. He was responsible for my grandmother’s care for the last five years of her life. They were very close. My dad was different after this loss.

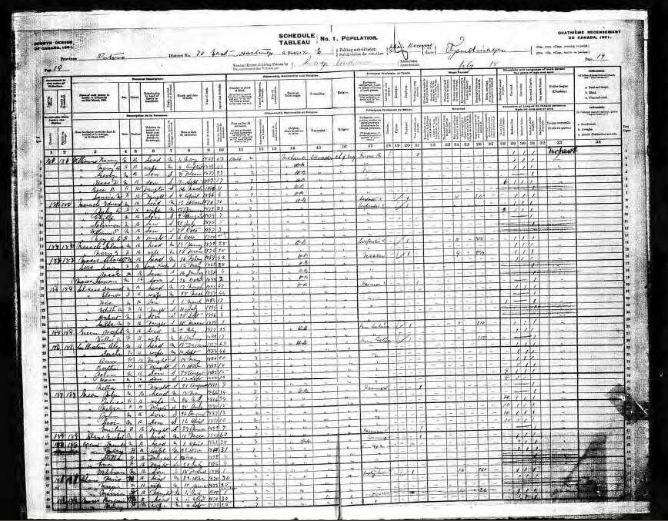

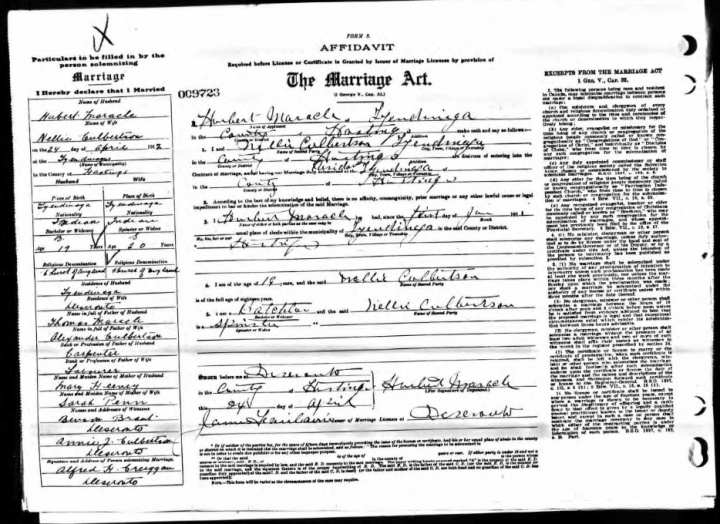

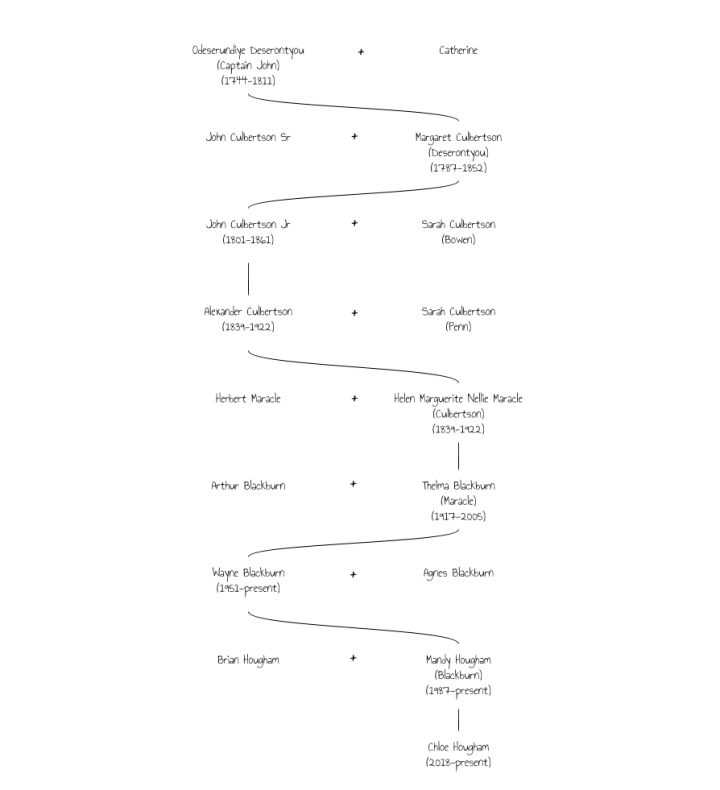

But with her death, Dad started to dive into his family heritage. Like deep dive in. So now I’m following in his footsteps–which is great, because he did a lot of the grunt work for me. From him I learned that my great-grandmother’s name was Nellie Culbertson. Nellie was listed on the 1901 census as a 9-year-old on the Tyendinaga Reserve of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte.

But how did she get there?

From her marriage license to Herbert Maracle, I discovered that Nellie’s father’s name was Alexander Culbertson, the son of John Culbertson Jr, who was the son of Margaret Deserontyou, who was the daughter of Captain John (Odeserundiye) Deserontyou, who lived from 1744-1811.

Family traces in Canadian history

Captain, you say? Captain of what? Captain John (Odeserundiye) Deserontyou was one of the war chiefs of the Mohawks on their land in the Mohawk Valley of mid-New York State. They allied with the British during several wars, including the American Revolution, fighting to keep their land. They lost the war, and the United States of America was formed. With this loss came the destruction and occupation of their farms and homes in the Mohawk Valley by the Americans. The treaty that ended the war made no provision for the people of the Mohawk Valley to return home, so they fled to Lachine, Quebec in 1777.

It was Captain John and Thayendanegea (also known as Joseph Brant, another Mohawk military and political leader) who met with the governor of Canada to discuss the loss of land experienced by the Mohawks and where they would go. As their people suffered poor conditions in Lachine, John and Joseph made a deal with the Crown and separated; Captain John Deserontyon took 20 Mohawk families to the Bay of Quinte, and Joseph Brant took the rest to the Grand River in southern Ontario (modern day Brantford, ON and the Six Nations reserve).

On May 22, 1784, families of the Wolf, Turtle, and Bear Clans landed on the shore of their 7000- acre reservation (land purchased for them by the British from the Mississaugas), to basically start over. They named the land after Joseph Brant, Thayendanegea, calling it Tyendinaga (where my great-grandmother Nellie lived). Captain John’s personal property was later established as a village and named Deseronto, Ontario. It’s still located just outside of Belleville, and in the middle of the Tyendinaga Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte reserve.

Skip forward to Canadian Confederation in 1867, and the passing of the Indian Act in 1876. This act defined how the Government of Canada interacted with Indigenous peoples. It enforced Euro-Canadian standards of civilization. Bet you can see where we’re headed…

That’s right, residential schools. In 1884, an amendment to the Indian Act made attendance at day schools, industrial school, or residential schools compulsory for all First Nations children to the age of 15. Because of the rural nature of First Nation communities, many families had no local options, and were forced to comply by sending their children to residential schools that were funded by the government, far away from their homes. These schools were run completely by Christian churches, with strict rules to assure limited contact and communication with their families back home.

This amendment was strategic in nature, as the hope was to “civilize” the population of First Nations children by removing them from their race and culture, and immersing them in the “superior” British race, culture, and religion.

The sovereignty of the Indigenous people was no longer recognized–though it barely existed in the first place. They were used by the colonialists: used for their knowledge of the land, and as soldiers in wars that never should have involved them or their land. And once the “usefulness” of the Indigenous people to the white man decreased, the British focused on establishing their own permanence in this land that belonged to the Indigenous people–a permanence they sought to obtain through cultural genocide.

Residential schools were run for over 100 years (the last one closed in the 1990s)! Even in the 1960s with the “Sixties Scoop,” police officials based their assessment of the welfare of Indigenous children on Euro-Canadian values. They deemed traditional diets of game, fish, and berries insufficient for their development, and removed those children from their families, placing them into custody.

Processing in real time

So now I sit here, newly educated about the treatment of my family, and my people, and I am hurting. As a new mom, I hurt for the families that were ripped apart by my country’s government. I hurt for the loss of identity those children experienced–removed from the culture and way of life that they knew. They were given a new life, one that took away their opportunity to return to their home, and left them in a place to experience constant racism. We see the results of this cultural genocide today with the disportionate experience of PTSD, alcoholism, substance abuse, and suicide among Indigenous peoples. I cannot relate to this degree of isolation, but I hurt for them.

My hurt quickly leads to feeling conflicted…

For 10 years I have worked as a full-time Christian missionary. I’ve been to many countries for the purpose of sharing Christ with those that have not heard of him and his gospel. I saw what I did as good–bringing hope, and peace, and the love of God to people who have never known. And now, as I enter this new place of empathy and identity, I wonder about my motives, the abuse of my “white authority,” and any association I might have to this colonial kind of “mission.”

Though I am disgusted by the pride, greed, and the evil that I see in my “spiritual family” that did this to my actual family, I have to ask the question: Is this Jesus that I see, or is it the failures of us who claim to follow him?

"*" indicates required fields

Share this!

About the Author