[Editor’s Note: When God created the world, he saw that “it was good.” In this series, we want to explore how our faith in Jesus helps us celebrate and enjoy what’s good in creation––but also work as stewards to help it thrive to its fullest potential. Caring for our planet, including plants and animals, fungi and microbes, ecosystems and people, is a high calling from God––a calling in which we can engage out of love and not fear. The gospel gives us hope that what is broken can be restored, and even now, we can enjoy what has been given to us. Join us as we #celebratecreation.

This article was written by Stephen Luk, who has been fascinated with insects since a young age, teaching himself to find and identify them. He completed his MSc at the University of Guelph Insect Systematics Laboratory, and his passion for insects has taken him from the Amazon rainforest to the Mojave Desert. Steve also enjoys birdwatching, photography, travelling, and science fiction.]

A Lifelong Pursuit

I was too young to remember my first insect encounter. But I can visualize myself leaning over, eyes wide in wonder, as my father shows me a stick insect in the mountains beyond Hong Kong. He recounts this story with delight, always tagging on another, which I do recall: finding my first praying mantis at a beach. These were the sparks that set me off on what has been an awe-filled, lifelong pursuit.

My inordinate fondness for insects always had me lagging behind during group hikes or wandering about during free time at church camps. I was withdrawn, yet my quests invariably drew others’ curiosity. As my experience and Christian faith developed, so too did my mission: to share my knowledge of insects, not for self-gratification but for the glory of God.

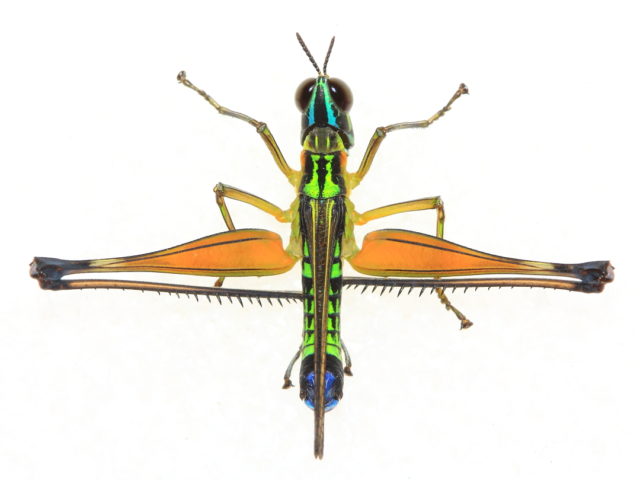

I believe that Christians are lifelong learners of God, including his self-revelation in all his handiwork. Which surely includes insects, though I acknowledge the thought may “bug” some. Still, I invite you to track with me briefly. I want to instill even a small appreciation of how creeping things are exquisite creations. I want to share glimpses of how insects point to their Creator.

Insects declare God’s diversity

Like the starry heavens declaring the glory of God, the astronomical diversity of insects manifests the Maker’s grandeur. The Smithsonian Institute estimates the global insect population at 10 quintillion, or 1 followed by 19 zeros. Entomologists (people who study insects) have named over a million species, while speculating that five to ten times as many await discovery. Consider Crane Flies (family Tipulidae), those summer wraiths often mistaken for oversized mosquitoes (note: they do not bite!). Prominent entomologist C.P. Alexander named about ten thousand species of crane flies—roughly one per day over his career—and an army of researchers continues to pour lifetimes of study into myriads of smaller insect families. Whether at the Guelph Insect Collection or further afield, I well understand this endless diversity. Even as a conversant entomologist, I am constantly seeing unfamiliar insects.

Insect diversity struck me most when I was deep in the jungles of Ecuador, observing different kinds of insects on plant after plant. One can spend hours at a single site, because an individual rainforest tree can host hundreds of insect species. Among my favourites were Pleasing Fungus Beetles (family Erotylidae). These dazzling insects come in bewildering colours and forms, from technicolour to pearlescent, domed to limpet, oblong to teardrop. Each beetle, it seemed, was sculpted, signed, and set upon the leaves by an invisible hand! From Fungus Beetles to Dragon Mantises, insects are God’s love of diversity on display.

Insects declare God’s power

This spring, the Eastern United States will witness an insect spectacle: billions of Periodical Cicadas (Magicicada species) appearing in unison after spending 17 years as subterranean nymphs. For several weeks, ubiquitous “Brood X” cicadas will saturate the air with their mating trill. By summer, the bugs will have laid eggs and expired. While a dozen mostly smaller broods make staggered emergences during other years, Brood X will vanish until 2038. (I am disappointed to be missing the latest event, due to probable border restrictions!)

Although periodical cicadas are absent from Canada, we will see swarms of our own. Each summer around Lake Erie, Burrower Mayflies (family Ephemeridae) erupt in such prodigious numbers that snow plows have been used to clear the roads of their corpses. Immature mayflies inhabit lake beds, converting organics into energy for their ephemeral adult flight. Like periodical cicadas, they emerge by the millions to overwhelm predators, allowing survivors to reproduce.

Insect swarms of biblical proportions have evoked awe and fear throughout human history. It’s easy to believe that they are invincible, even foes to be opposed. Yet, these animals were created for unique, albeit sometimes seemingly negative, ecological roles. They are powerful, yet more fragile than we think. Burrower mayflies, dwellers of clean water, nearly vanished from Lake Erie due to mid-1900s pollution. Several localized periodical cicada broods have gone extinct, their habitats presumably destroyed. Similarly, the hordes of Rocky Mountain Locusts (Melanoplus spretus) that used to descend over the Prairies (yes, Canada had locusts!), persist now as remains, frozen in a glacier in Montana. Just as spawning salmon fertilize temperate rainforests after death, swarming insects unlock and deliver nutrients to ecosystems. We may not welcome their invasions, yet I wonder how creation might groan and suffer if they were to be gone for good.

Insects declare God’s care

If you have read to this point—fantastic! Hopefully the talk of swarms has not spoiled your appetite, especially because we have insects to thank for our food supply. Behind our produce is a six-legged workforce: fresh fruits and coffee are pollinated by bees and wasps, cocoa by a tiny Biting Midge (Forcipomyia species), certain nuts by beetles, and exotic fruits—such as papaya and dragon fruit—by moths. In God’s everywhere-grace, insects not only signify his diversity and power, but are also agents for his care of humanity and all creation.

In God’s everywhere-grace, insects not only signify his diversity and power, but are also agents for his care of humanity and all creation.

Undeniably, some insects cause harm and pestilence. But untold more mediate the well-being of our Father’s world. Lady Beetles and lacewings bust damaging pests. Caterpillars and Leaf-cutter Ants check vegetation against overgrowth. Sexton Beetles and Lesser Dung Flies reduce waste matter so we’re not knee-deep in rotting plants—or worse. Miniscule springtails (not insects, but included for discussion) maintain soil health and are linked to that ineffable but signature smell of spring. Even mosquitoes, however maligned, can feed bats at 1,000 mozzies per-bat-per-hour. (A statistic for which I am grateful; woefully for an entomologist, I react badly to mosquito bites.) The list of insect benefits is endless.

Then consider how each and every labouring critter is superintended by a watchful Master—in whom all things hold together—including 10 quintillion insects, alive and doing his bidding.

Insects, for his glory and to know him

While we wait for God to restore all things, creation is sin-stained and strife-filled. There’s a saying that nature is “red in tooth and claw”—and insects are arguably the cruelest of all. Yet, were we to ask the insects, and let them teach us, we would still peer into the greatness of one who designed this intricately complex universe. One who made insects ultimately to praise him, and to be enjoyed and investigated by his image-bearers. Whatever your relationship with insects, may you behold with eyes wide open—as I did in my childhood moments—the one who has made himself known in all the things that have been made.

"*" indicates required fields

Share this!

About the Author